Conservation, Wildlife, and Art

Can a work of art help wildlife species?

This museum features animals from around the world that have been or are being helped by funding from artists and their works for many years. Art is fundamental to our humanity and inspires people to action. Not only does art bring joy to observers and artists, but it also helps express our values. Art can move people on an emotional level and inspire them to love and protect the natural world and special places. Our museum dioramas feature original artist murals depicting specific habitat scenes for each species displayed in the dioramas. These special paintings are educational and can inspire viewers to appreciate nature and wildlife.

Early artists of European descent ventured across North America in the 1800's, painting landscapes and wildlife, showing the wondrous creatures out west and the decimation of different species. These art works brought attention to the plight of overharvesting, habitat destruction, and general disregard for the natural environment. Carl Rungius, Wilhelm Kuhnert, Bruno Liljefors, and Richard Friese were noted for their profound influence on artists following in their footsteps, bringing real-life images to the eastern observers, and helping move decision-makers to recognize the need to make changes to save the magnificent wildlife that was once abundant in the new American nation. Art has an incredible ability to point out what cannot be seen firsthand. The painting of a bison herd that has been lost influences how the past is seen and how the future might be impacted. Wilderness became a treasured amenity to the growing urbanization of the early settled parts of the country. Romantic appreciation for the wilderness through artists paintings helped create national nature preserves and parks. Yosemite and Yellowstone parks were set aside for future generations to enjoy the wildlife and untamed wilderness. Politicians were moved to create the U.S. Forest Service, wildlife reserves, and national monuments.

Artists following in the footsteps of Lewis and Clark reiterated the changing conceptions of the wilderness in the images they created. Early artist-naturalists, including Georg Catlin, Karl Bodmer, and John James Audubon, set out to document the wildlife of the new continent. This scientific approach to recording imagery of wildness and animals created a romantic sensibility to the American wilderness and nature as a source of personal renewal and an alternative to the disenchantments of modernity. These wildlife works show North America as a continent full of amazing animals and a component of the national identity. Art moved people to take action to preserve this most precious resource.

Since 1934, when Ding Darling submitted and won the first annual Federal Duck Stamp Painting Award, Ducks Unlimited has sponsored duck stamp painting prints as auction items at their chapter banquets as fund raisers for the organization, bringing in millions of dollars for conservation efforts. The duck stamp sales have generated $1.2 billion for wildlife wetland habitats, impacting over 6 million acres of prime waterfowl habitat that also benefits all kinds of wildlife. The national duck stamp contest engages hundreds of artists from around the country competing for the current year's duck stamp image.

An Artist’s Journey Mainly in Watercolor

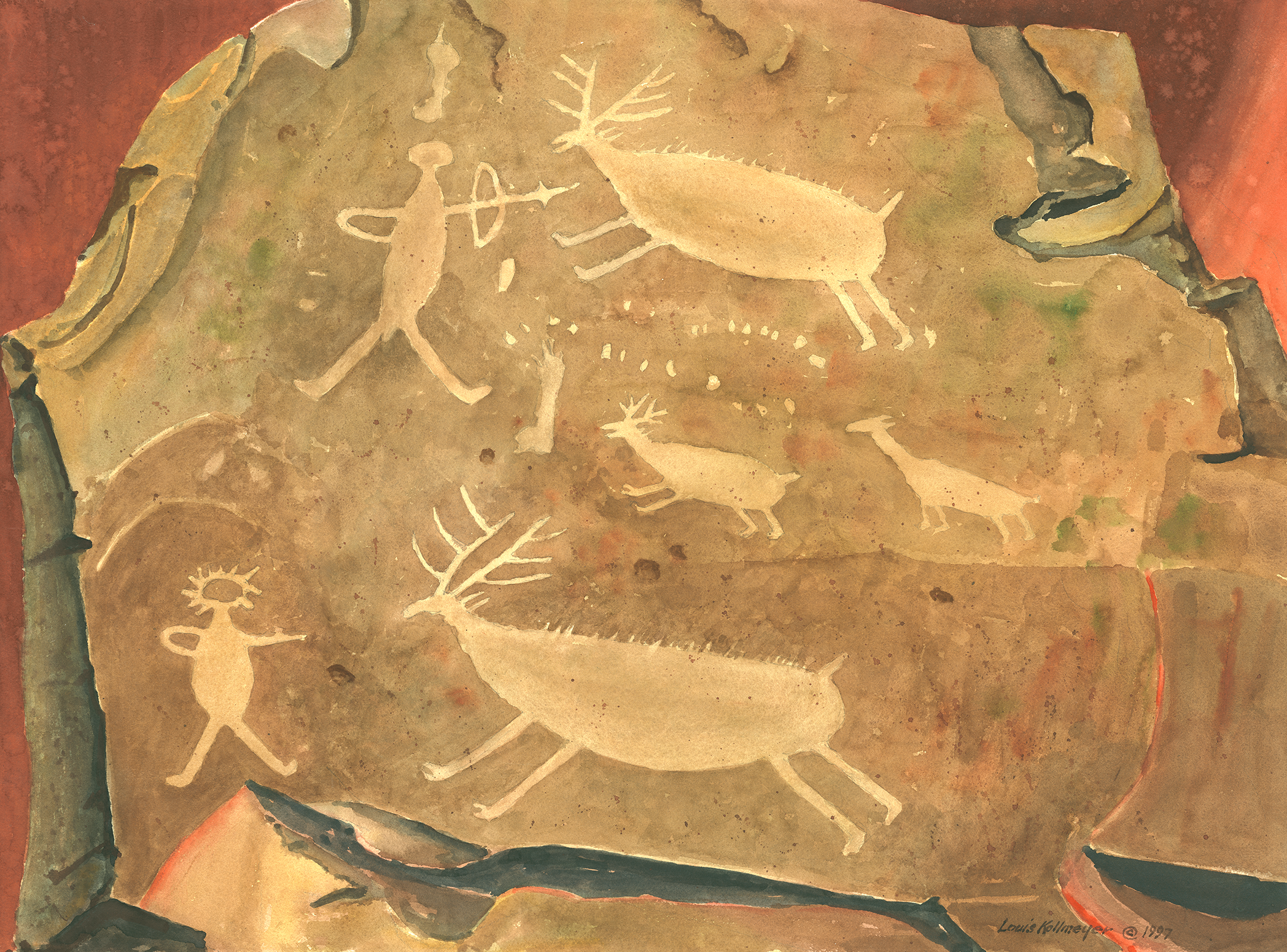

Louis A. Kollmeyer

Louis Kollmeyer is a Signature member of the Northwest Watercolor Society. He has received a number of awards and other honors. His paintings have been in 42 invitational and group shows, in over 50 juried exhibits, and 20 one-man shows. Two paintings were included in the Americans in Paris Exhibition in 1976, a Bi-Centennial of contemporary American painting.

Watercolor is Kollmeyer’s main medium, used in basic and experimental ways. Most of his concepts deal with the landscape environment, concentrating on earth forces and movement, color, and other design elements, rather than on literal transcriptions. In recent years he has also done a series of paintings based on prehistoric Indian rock art of the Columbia River region.

Power and Movement - Sculpture

Jerry McKellar

Twenty years ago, Jerry McKellar concentrated on root canals, crowns, and fillings in this thriving private dental practice in Colville, Washington. He had graduated from the University of Washington in 1969, spent two years with the Army Dental Corps, and then set up a practice with his wife Gayle, a dental hygienist he’d met in school. Life, however, took an interesting turn in 1987 when McKellar cast his first limited-edition sculpture entitled Startled. No one, however, was more startled than McKellar who found his love of art so strong that, by 1994, he began to devote himself to it on a full-time basis. Although the transition sounds a bit absurd, he finds that the intricate three-dimensional work of dentistry furnished good basic foundations for his sculpting. In fact, he has no formal art training other than a few patina classes. “Part of dentistry has to be quite artistic for the work to be good,” says the 63-year-old McKellar. “It does transfer over.”

These days Mckellar thinks big, but not in the cliche sense. but not in the cliche sense. With his life-size bronzes and monuments gracing public places and private collections from New Mexico to Vermont and Colorado to Washington, he savors sculpting people and wildlife in three-dimensional, larger-than-life formats. “ I’m doing a lot more life-size or larger pieces these days, and it’s awfully exciting to have those pieces out there long after [I’m] gone, “ says McKellar, who still makes his home in Colville. “I am quite humbled that people appreciate my work enough to have it made to that scale.”